This may occur through specific types of therapy, such as cue exposure therapy. Because most people in recovery cannot realistically eliminate every cue associated with their addiction, it becomes critical to reduce the power of these cues. With repeated cue exposure, and without engaging in addictive behavior, these cues lose the power to induce craving.

The "cues" associated with addiction (the sights, smells, locations, people, etc.) are understood as conditional stimuli. He is not doomed to ride public transportation for the rest of his life!Ĭue exposure therapy is one type of addiction treatment that relies on classical conditioning.

If this person repeatedly gets into his car after work, and does not smoke marijuana, his cravings will eventually subside. Let's return to our previous example of a person who smokes marijuana in a car after work. Eventually the bell will no longer elicit salivation. Research has demonstrated that if we ring the bell many times, without food, the paired association ends. Cravings frequently result in relapse.įortunately, this learning principle has some helpful recovery implications. This is the same for the addict and the car.

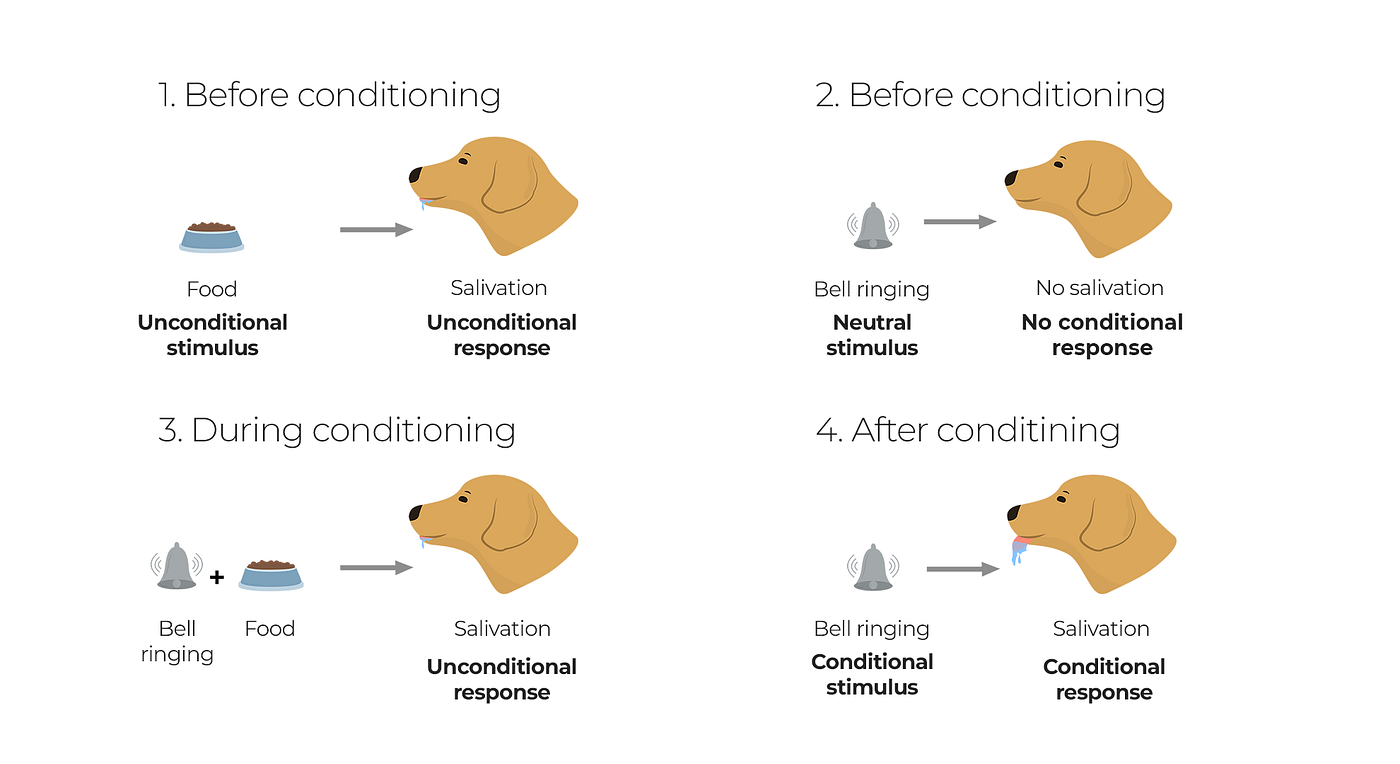

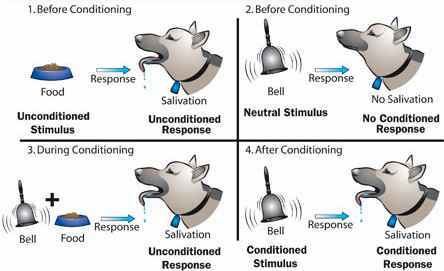

Remember how Pavlov's dogs began to salivate at the sound of the bell? We could say the bell created a craving for food. Once the car has become a conditioned stimulus (a cue), the car itself can now trigger powerful cravings. Thus, the car signals marijuana is on its way, just as the bell signaled to Pavlov's dogs that food was coming. The car and marijuana form a paired association. For instance, suppose someone always smokes marijuana in the car on the way home from work. These cues can result in a relapse because the brain linked the cues and the addiction. Food was on its way! Likewise, certain cues (also called relapse triggers) have a powerful effect on addicted persons. So what do dogs and bells have to do with addiction? Recall that in Pavlov's experiment, the bell served as a cue to the dogs. Eventually both the food and the bell elicited the same response, i.e., salivation. They learned! This learning occurred because of the paired association between an unconditioned stimulus (food) and a conditioned stimulus (a bell). The dogs had been conditioned that the bell meant food is on its way. Eventually, Pavlov's dogs began to salivate at the mere sound of the bell, even when Pavlov did not present the food. Pavlov formed a paired association between an unconditioned stimulus (dog food) and a conditioned stimulus (a bell). This is because the dogs learned (they were conditioned) that when the bell rang, food would arrive. Unlike food, which is an unconditioned stimulus, the bell became a conditioned stimulus. We could say he paired a bell with the arrival of food. In one of Pavlov's experiments, he rang a bell every time he fed some dogs. Now we come to the learning part of classical conditioning (a bit more complicated). You don't need to learn to salivate upon seeing food (no conditioning was required). This simply means it is an automatic reflex or response.

You didn't need a psychologist to tell you that! Salvation at the sight of food is an unconditioned response. For instance, if you see food (a stimulus), you will salivate (a response). Sometimes people also call it Pavlovian conditioning.Ĭlassical conditioning means that a specific stimulus causes a specific response. It was during these experiments that he discovered an important learning principle that we now call classical conditioning. During 1849-1936, Pavlov was investigating the automatic reflexes of animals. We strive for accuracy and fairness.A Russian physiologist named Ivan Pavlov discovered classical or respondent conditioning (somewhat accidentally). Their first son died suddenly as a young child, but they proceeded to have three more sons and a daughter. The couple had virtually no money in their early years together, and often lived separately until their finances stabilized. In 1881, Pavlov married pedagogical student Seraphima Vasilievna Karchevskaya. He remained devoted to his lab work until his death from double pneumonia on February 27, 1936, in Leningrad. Pavlov softened his tone in the last years of his life, perhaps due to increased government support of scientific research. He toed a dangerous line with his criticism of Communism after visits to the United States in the 1920s, though he escaped prosecution due to his standing as one of Russia's preeminent scientists. Pavlov openly decried the war-torn conditions of his country after the Russian Revolution of 1917. Although he was notably dismissive of psychology as a pseudo-science, his research helped lay the groundwork of several important concepts in the then-nascent discipline. Later in life, Pavlov applied his laws to the study of psychosis, arguing that some people withdrew from daily interactions with others due to the association of external stimuli with a harmful event.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)